|

Versione italiana |

An illogical term and a very muddled concept!

The European regional policy discourse seems to have more than its fair share of confusing and ambiguous terminology. “Inner Peripheries” is a classic example. Of course, at face value, the two words contradict each other; how can a locality be both “on the edge” and “inner”? We would not be the first to observe that such lack of clarity seems to be attractive to policy makers and practitioners, because it allows for great elasticity in terms of interpretation and policy implementation! A more positive response is to try to “deconstruct” the concept into a set of themes, and to understand how it is the “child” of certain changes both in the policy and academic discourses, and, more fundamentally, of real-world socio-economic trends.

The Changing Concept of Peripherality

Broadly speaking what has happened over the past two decades is that the original (spatial) meaning of the term “peripherality”, which was all about the economic and social costs and penalties faced by locations at a distance from the main “hubs” of economic activity in Europe, where the benefits of agglomeration economies were maximised, has become muddled up with a range of “figurative” meanings, which are to do with socio-economic “marginality” in an aspatial sense. It is perhaps emphasizing, before we go any further, that we do not see marginality a synonymous with peripherality. The former despite its etymology is generally used to denote socio-economic rather than locational characteristics.

During the 1980s and ‘90s considerable efforts were made to measure spatial peripherality, using various models, especially one which used Newtonian gravity as an analogy for “economic potential” (Keeble et al., 1988; Copus, 2001; Espon, 2004). Many very attractive maps were drawn, the parameters of the models were carefully tested and adjusted using different forms of transport to explore the assumed effects of “peripherality” on different aspects of economic and social activity. Those involved in this research were very aware that such adjustments could have the effect of either accentuating continental scale differences between the outer-most regions of Europe and the core regions (sometimes known as “the blue banana”), or of highlighting smaller scale differences within countries (Schürmann and Talaat 2000; Espon 2009). Such “enclaves” of peripherality were particularly striking if they were identified in what is commonly known as “Central Europe”. However it is fair to say that, since this research roughly coincided with the accession of Spain and Portugal (1986), and Sweden, and Finland (1995), the focus of the policy debate was very much upon the kind of peripherality experienced by the sparsely populated regions of the North and the West. In fact, although the peripheral regions of the Iberian Peninsula qualified for designation under Objective 1 of the Structural Fund, the better performing Nordic regions were given a new designation (Objective 6) on grounds of their peripherality.

Even at this stage, when it was widely assumed that the effects of peripherality could be predicted as a function of distance from centres of economic activity, academics were pointing out that despite the sophistication of the models and the maps, we understood much less about the socio-economic processes which translated these into local variations in socio-economic performance. Thus according to Peter Gould (1969: 37) peripherality is “…a slippery notion…one of those common terms everyone uses until faced with the problem of defining and measuring it".

Since the turn of the century three things have changed:

- The EU has grown to 28 Member States, and the new ones have all been in the East, where there is no natural boundary (like the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean). This poses a question of “where do you draw the line” (in terms of territories and data to include), for the kind of modelling and mapping of peripherality which had previously been carried out. It has also switched the political focus from the kind of peripherality experienced in the North and West to the more localised “enclave” pattern of Central Europe.

- Secondly, during this period there has been a gradually increasing awareness that there have been, or soon will be, subtle but very important changes in the role of physical distance in determining patterns of economic activity and prosperity. To express it another way, the agglomeration economies of the core, and the disadvantages of remoteness are gradually and partially being reconfigured. The most extreme interpretation of this change argues that spatial proximity is just one of a range of different forms of proximity, of which non-spatial or “organised” kinds, involving (for example) social interaction and trust, or shared knowledge and information, or reflecting institutional or governance structures, are increasingly important (Torre and Rallet, 2005).

- The third development which has affected the concept and meaning of the term “peripherality” is partly a consequence of the preceding two. This is the popularity among both academics and the policy community of using the (spatial) concept as an analogy or metaphor for poor socio-economic performance, so that any lagging region is described as a “periphery” regardless of its location, and justified in terms of (inputed) non-spatial forms of proximity (Copus, 2001). According to Bock (2016 p5) “Whereas in the past, the main cause was ascribed to geography, this has changed in the sense that the lack of resources is now explained as resulting from a lack of socioeconomic and political connections (‘connectivity’) and, hence, of relational ‘remoteness’ that is not necessarily bounded to geographical location…Geographical remoteness, as such, therefore does not cause marginalisation, nor does central location promise prosperity”. In this way the causal link between peripherality and performance is, in effect, reversed.

From the perspective of 2016 it is important to take the complex evolution of the concept of peripherality into account when trying to understand what is meant by the term “inner periphery”. Often it is only by a careful reading of the context that it is possible to establish whether a writer or commentator has a spatial or metaphorical concept of peripherality in mind, or a hybrid of the two.

The origin of the Inner Periphery Concept

Whilst the term “Inner Periphery” is vaguely familiar to many who work in the field of regional development, the literature relating to it is sparse, and difficult to find. Early applications of the term to Appalachia (Walls, 1978; Hanna, 1995) and Lesotho (Weisfelder, 1992) are associated with the global core-periphery system described by Immanuel Wallersten (1991). More recently, Vaishair and Zapletelova (2008) in their study of small towns in Moravia use the term to describe sparsely populated areas along national borders and where the topography is hilly. They also refer to the Alps as being an inner periphery “from a West European view” (p72). Similarly, in a Russian context Kaganskii (2013) defines the inner periphery in terms of rural areas which are relatively close to centres of economic activity, but nevertheless lagging themselves.

As far as we are aware the term “inner periphery” (or in this case “internal periphery”) was first used in a European policy document in the background report prepared for the Territorial Agenda 2020 meeting in Godollo, Hungary in 2011 (Ministry of National Development and Vàti Nonprofit Ltd., 2011). The description is quoted below at length, since it seems to be the starting point for the subsequent discussion of inner peripheries:

“Internal peripheries are unique types of rural peripheries in European terms. The vast majority of these areas are located in Central and Eastern and in Southeast Europe and most of them have serious problems. Their peripherality comes primarily from their poor accessibility and paucity of real urban centres where central functions can be concentrated. These problems derive from the historical under-development of these territories and they are often compounded by specific features of the settlement network or social characteristics. The main problems of these areas are their weak and vulnerable regional economies and their lack of appropriate job opportunities. In these circumstances negative demographic processes, notably out-migration and ageing of the population, are getting stronger and stronger. These trends create the conditions for social exclusion, and even territorial exclusion from mainstream socio-economic processes and opportunities. While rural ghettoes are mainly a result of social factors, ethnic segregation can make difficult situations worse. This is the case, for example, in rural peripheries of Slovakia, Hungary and Romania where there are areas with high proportions of Roma population.” (Ministry of National Development and Vàti Nonprofit Ltd., 2011: p. 57)

Later in the document the authors call for analysis of internal peripheries by the Espon programme (Ministry of National Development and Vàati Nonprofit Ltd., 2011: p. 87).

There is no reference to “internal peripheries” in the final TA2020 text1, which is presumably why the Espon Geospecs project concluded “The concept of Inner Peripheries (IP) as such is new in the European policy arena, as illustrated by the fact that there are no policy documents dealing explicitly with it…” (Espon Geospecs, 2013: p. 1). The Geospecs team also find no academic literature, and proceed to base their report on interviews with policy stakeholders in Belgium, Netherlands and Germany. They conclude that inner peripheries are defined by socio-economic rather than geographic characteristics, or distance from centres of economic activity. Often they are affected by economic restructuring; the loss of a key industry and high unemployment. As such, unlike true geographic specificities they are mutable or transient, rather than permanent.

Generally speaking the Geospecs report illustrates to risk of abandoning spatial (in)accessibility as a defining feature for inner peripheries: It becomes impossible to distinguish inner peripheries from any other kind of lagging rural or semi-rural area. In commissioning a new report on Inner Peripheriesè2 the Espon 2020 programme recognise and avoid this pitfall by drawing on a growing body of work relating to access to services of general interest (Sgi). This is more than a question of choice of indicators – it shifts the concept of inner peripheries away from the concept of “economic potential” and towards the quality of life, or well-being of rural inhabitants. This in turn links them to demographic issues, such as rural-urban migration, and ageing. It also resonates with the impacts of austerity on service provision, and the longer-term effects of new public management, universal service obligations and “territorial equivalence”. This seems to suggest that the concept of inner peripheries which is emerging is not simply a Central European analogue of the kind of “economic potential” peripherality observed in Northern and Western Europe, but rather one which has more in common with the discourses on social exclusion and well-being.

The Italian policy initiative to support “Inner Areas” (Lucatelli et al., 2013, Mantino and De Fano 2015) has much in common with the concept implied by the recent Espon project call. Here too, the primary definitional indicators relate to access to services of general interest. However an additional source of terminological confusion arises between the Anglophone research tradition, which is used to the idea that the “periphery” is indeed around the (Northern and Western) edges of the country, and that of the Mediterranean and Iberian countries, where major cities are located on the coast, and peripherality is associated with “the interior”, or “inner areas”.

Do Inner Peripheries exist elsewhere in Europe?

In the final section of our paper we will speculate about the potential utility of the “inner periphery” concept as a policy targeting tool in two Western European countries in which it has not so far been adopted, Spain and the UK (Scotland).

From the European point of view, Spain, as a whole, is clearly located in the periphery. Considering the geography of Spain, the classical concept of remoteness seems valid, with large regions that are characterised by their location and distance from the main centres of population and economic activity. The topography and the way in which the infrastructure networks have developed throughout history contribute significantly to the configuration of these regional peripheries thus generating a map of contrasts. Although “a land of classical peripheries”, there also seems to be evidence of the existence of territories with a central location with relative problems of access to services of general interest, and situations of socio-economic deterioration, that cannot be explained by geographical location. To illustrate this we will refer to the region of Valencia, one of the 17 so called “Autonomous Communities” with extensive and exclusive powers in policy making, including health, social services, education or land use policies.

Valencia is a region of contrasts with an unbalanced territory. The region shows a strong concentration of population, economic activity, infrastructure, equipment, and utilities in most of the coastal stretch of the provinces of Castellon and Valencia. From the metropolitan area of Valencia, this axis development unfolds forming an inverted "Y" that reaches the tourist and industrial southern region. By contrast, most of the inland part of the region is composed of a succession of lagging rural areas showing the classic set of characteristics of rural peripherality: depopulation, ageing population, local fragmented labour markets and precarious access to goods and services of general interest, among others.

Although the region is clearly divided into two parts with respect to the traditional concept of peripherality (interior and coastal, basically), some areas well served from the point of view of traditional peripherality show poor values for indicators of quality of life and access to services of general interest. Without denying the presence of the classic dichotomy between central and peripheral areas at the macro-level, a closer look allows us to observe the existence of geographically central enclaves that show indicators of access to services of general interest that score well below the standards of surrounding central areas. Classical peripherality is not evident in these enclaves; they are well connected from the point of view of accessibility (some of them at the centre of major regional corridors). There must exist, therefore, other socioeconomic factors of non-geographic nature that help explain the poor performance of these areas in terms of economic welfare.

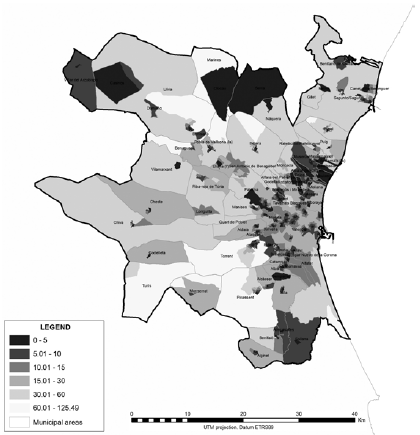

The Metropolitan Area of Valencia is the largest urban conglomerate in the region. It contains a central municipality, the city of Valencia, and 75 municipalities totaling approximately 1,800,000 inhabitants. Pitarch (2013) has calculated for this central territory a separation index consisting of measuring the time distance between each census district and all major public facilities (health, education and basic social services). The results of the analysis (Figure 1) show significant distortions with respect to a typical center-periphery model in which the most central areas would show better accessibility rates in all indicators. By contrast, maps show a mosaic of accessibility that clearly points to the existence of census districts well located from the geographical point of view, that have low performance in relation to one or more analysed services. Municipalities that have remained in less profitable functional or productive specialisations, seem to be cases of inner peripheries, where residents experience increased difficulties in accessing basic services and, therefore, require particular attention when designing and implementing public policies which respond to their particular needs.

Figure 1 - Metropolitan area of Valencia. Time in minutes (Spatial Separation Index) to the nearest basic social services centre

Source: Pitarch (2013)

The densely populated “Central Belt” of Scotland, stretching from Edinburgh in the east to Glasgow in the west, constitutes a conurbation with a population of approximately 3.5 million (two thirds of the Scottish total) and is a substantial free-standing economic hub. The Central Belt is separated from cities in the North of England, such as Newcastle and Lancaster by a sparsely populated area within the administrative regions of Scottish Borders and Dumfries and Galloway. Although the Highlands and Islands situated to the north and west of the Central Belt have long been recognised as peripheral (in the conventional, spatial sense), the rural area adjoining the border with England exhibits many of the characteristics of an “inner periphery”.

Scottish Borders and Dumfries and Galloway are traversed by major trunk road links to England, but the local road network is relatively sparse and unimproved, and the small towns within the area provide only basic services. Drivetimes and public transport travel times to key local services (doctor, petrol station, post office, primary and secondary schools and a retail centre) are published as part of the Scottish Government’s Index of Multiple Deprivation3. A significant proportion of the Scottish Borders and Dumfries and Galloway comprises data-zones4 which are in the least accessible quartile of rural Scotland; more than 40 minutes by public transport, and more than 15 minutes by car from the nearest local services (Copus and Hopkins 2015: p. 22, 24). It therefore seems reasonable to describe this area as an “inner periphery” in terms of its accessibility to Sgi.

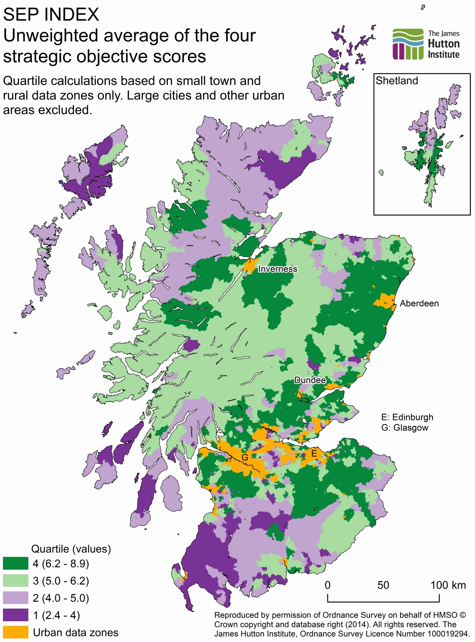

The general socio-economic performance (Sep) of rural Scotland was recently assessed and mapped at a data-zone level, using 20 indicators carefully chosen to represent four of the five “strategic Objectives” of the Scottish Government’s National Performance Framework5 (Copus and Hopkins 2015). These four strategic objectives are all socio-economic: they are “Wealthier/Fairer”, “Safer/Stronger”, “Heathier”, and “Smarter”. The methodology was very simple: First each indicator was converted to a set of scores from 1(worst performance) to 10 (best performance). Simple averages were then calculated for each of the four objectives. The four objective scores were then combined, as a simple average to create an overall “Sep score”6.

Figure 2 shows that much of Dumfries and Galloway is in the bottom quartile in terms of its overall Sep score, and most of the remainder is in the second quartile. The poor performing area stretches north into adjoining Ayrshire. To the east, in the Scottish Borders, the picture is more mixed, some data-zones especially along commuter routes to Edinburgh, performing relatively well - in the third and fourth quartile. Examination of the individual indicators which contribute to this overall performance index shows that Dumfries and Galloway, and to a lesser extent Scottish Borders faces a range of challenges, particularly relating to human capital – depopulation, ageing, higher than average rates of ill-health, lower levels of economic activity, and a disproportionate incidence of lower qualified workers in low status occupations. Again this profile tends to support the description of Dumfries and Galloway, together with parts of Scottish Borders, as an “Inner Periphery”.

Figure 2 - The Socio-Economic Performance (Sep) Index of Rural Scotland

Source: Copus and Hopkins (2014, p. 69)

Conclusions

The term “Inner Periphery” is a confusing and ambiguous one. There is a danger that pressing the analogy between peripherality and marginal socio-economic performance too far renders inner peripheries indistinguishable from lagging areas more generally. For this reason we suggest that the term is best reserved for areas which although not on the edge of the European continent are nevertheless “enclaves” of poor accessibility. In recent years the object of that accessibility is increasingly shifting away from the “hard” economic/competitiveness concept of “Economic Potential” which characterised early peripherality modelling, towards a softer, socio-economic focus on services of general interest and associated well-being for rural residents. We have argued that this second-generation peripherality concept can be a useful way to characterise “depleting” rural areas in the contrasting national contexts of Spain and Scotland.

References

-

Bock B. (2016), Rural Marginalisation and the role of Social Innovation: A Turn Towards Nexogenous Development and Rural Reconnection. Sociologica Ruralis Doi: 10.1111/soru.12119

-

Copus A. (2001), From Core-Periphery to Polycentric Development; Concepts of Spatial and Aspatial Peripherality, European Planning Studies, 9:4, 539-552

-

Copus A. and Hopkins J. (2015), Mapping Rural Socio-Economic Performance, a report for the Scottish Government [link] [Accessed 6th April 2016]

-

Espon (2004), Transport services and networks: territorial trends and basic supply of infrastructure for territorial cohesion, final report for Espon project 1.2.1. Luxembourg [link] [Accessed 6th April 2016]

-

Espon (2009), Territorial Dynamics in Europe: Trends in Accessibility, Territorial Observation No. 2, Luxembourg [pdf] [Accessed 6th April 2016]

-

Espon Geospecs (2014), Inner Peripheries: a socio-economic territorial specificity, Luxembourg [pdf] [Accessed 6th April 2016]

-

Gould P. (1969), Spatial Diffusion, Commission on College Geography, Association of American Geographers, Washington DC

-

Hanna S. (1995), Finding a place in the world-economy: Core-periphery relations, the nation-state and the underdevelopment of Garrett County, Maryland. Political Geography 14.5: 451-472

-

Kaganskii V. (2013), Inner Periphery is a New Growing Zone of Russia’s Cultural Landscape, Regional Research of Russia, 3:1, 21–31

-

Keeble D., Offord J., and Walker S. (1988), Peripheral Regions in a Community of Twelve Member States, Commission of the European Community, Luxembourg

-

Lucatelli S., Carlucci C., Guerrizio M. (2013), A strategy for the Inner Areas of Italy. Paper presented at the European Rural Futures Conference, Asti, Italy

-

Mantino F. and Fano G. (2015), New concepts for territorial rural development in Europe: the case of most remote rural areas in Italy, Paper presented at the XXVI Congress of the European Society of Rural Sociologist, Aberdeen August 18-21 2015

-

Ministry of National Development and Vàti Nonprofit Ltd. (2011), The Territorial State and Perspectives of the European Union, 2011 update, Background document for the Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020, presented at the Informal Meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development on 19th May 2011 Gödöllő, Hungary [pdf] [Accessed 6th April 2016]

-

Pitarch M.D. (2013), “Measuring equity and social sustainability through accessibility to public services by public transport. The case of the Metropolitan Area of Valencia (Spain)”. European Journal of Geography, volume 4, issue 1: 64-85. Issn 1792-1341

-

Torre A., and Rallet A. (2005), Proximity and localization. Regional Studies, 39 (1), 47–59

-

Vaishar A., and Zapletalová J. (2008), Small towns as centres of rural micro-regions. European Countryside 2,·70-81

-

Wallerstein I. (1991), Geopolitics and Geoculture: Essays on the Changing World System, Cambridge University Press Cambridge

-

Walls D. (1978), "Internal colony or internal periphery? A critique of current models and an alternative formulation." Colonialism in Modern America: The Appalachian Case 319-49

-

Weisfelder R. (1992), Lesotho and the inner periphery in the new South Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies 30.04: 643-668

- 1. [link] (accessed 6th April 2016)

- 2. [link] (accessed 6th April 2016).

- 3. [link] (Accessed 6th April 2016).

- 4. Data-zones are the standard small geographic unit for socio-economic analysis in Scotland. There are 6,500 data-zones in Scotland, and they have populations of between 500 and 1,000.

- 5. [link].

- 6. [link].