Introduction

In the context of the transition process that rural areas are currently facing, the prospects for future development essentially depend on an increasing interaction with urban areas, thus establishing a more communicative and collaborative relationship between producers and consumers. The creation of networks could open up a possible "third way" (Amin and Thrift, 1995), that allows the re-interpretation and re-adaptation of traditional models for endogenous and exogenous rural development (Lowe et al., 1995; Murdoch, 2000). These networks basically have two types of configuration: vertical and horizontal. Vertical networks mostly represent large scale food production chains and recall in some respects the configuration of the model for exogenous rural development, in which a sectoral approach prevails and the rural area is seen as a mere container of tangible and intangible resources that must be oriented on the demands from urban areas and the market. Horizontal networks, on the other hand, are inspired mainly by the model for endogenous rural development. They are based largely on the idea of sharing local resources and, more recently, also adopts new interpretations caused by changes in society, new food styles and new technologies, including those of digital communication (Sotte, 2006). The horizontality in the relationships between producers and consumers is one of the founding principles of initiatives such as collective buying groups (Rossi and Brunori, 2011) and farmers' markets (Aguglia, 2009).

Whether vertical or horizontal, the success of a network depends on the content, on the interactions of the actors within and on the type of relationships between them (Latour, 1986). But whereas in the vertical networks the subjects are bound by specialized and hierarchical relationships -hence the adjective "vertical"-, in the horizontal ones a variety of actors tend to operate on an equal basis and cooperate following principles of reciprocity and mutual recognition (Bourdieu, 1980). In this context, some proposals for innovative and alternative development that encouraged the creation of bridge relationships between rural and urban areas have found a place, especially in cases where it was possible to locate and establish a relationship based on the sharing of knowledge and innovation in situations that initially presented a high degree of fragmentation and internal diversity (Esparcia, 2014). Among the actors of this network system you may find, for example, producers who follow organic regulations or other practices that are considered alternative and/or sustainable from an environmental point of view and consumers who, through citizen engagement initiatives, are interested in learning more about the practices and meanings inherent in agricultural production.

Starting with the considerations of how the horizontal network model can become a potential catalyst for rural development, this article presents the case of Wwoof (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms) Italy, an association that promotes the free movement of volunteers in rural areas in Italy.

The Wwoof phenomenon in Italy

Wwoof is an example of a horizontal network in which the development and sharing of knowledge, information and innovation processes create a direct link between the countryside and the city. The organization was founded in 1971 in Great Britain, with the aim of promoting understanding and learning in the field of food production methods and the approach of the diverse "organic" world and "alternative" agriculture by creating opportunities for small farmers in the English countryside and the inhabitants of surrounding towns to meet and exchange knowledge.

The Association first extended into the Anglo-Saxon countries and has now grown to include more than 70 member countries worldwide with more than 50,000 volunteers (Ravasi, 2010), who receive food and lodging in exchange work on over 11,000 farms (Fowo data updated to 2010).

In 2013 an international umbrella organisation was formed to which most1 of the existing national associations refer, the Federation of Wwoof Organisations (FoWO), with the task to coordinate and support the movement in the world.

Wwoof Italy (WI) was founded as an informal organisation in 1999 in the Province of Livorno. In 2005 it was entered in the register of Associations for Social Promotion. Its objective, as stated in the charter is "to manage the movement of Volunteers (Wwoofers) nationally and globally in order to promote organic farming as a lifestyle."

The network nodes, in Italy as in other countries, consist of people (hosts) who have a family-owned and/or professionally run agricultural business (small-medium sized farms, agricultural cooperatives, family homes and eco-villages aiming at food and/or energy self-sufficiency, farm stays or farm campsites), in a place where people live and work together and where the volunteers (Wwoofers) can stay for a period of time and partake in seasonal labour for some hours a day. People can join the movement as hosts or as volunteers by registering on the website of Wwoof Italy and paying the annual membership fee (which in Italy is € 35).

Currently there are 654 registered hosts (data WI, 2015)2, that are present mostly in Tuscany, Emilia Romagna and Piedmont (Figure 1). Based on the number of host members, Italy ranks sixth in the movement worldwide, after Australia, the Usa, New Zealand, Canada and France.

Figure 1 – Distribution of hosts in Italy at regional level

Source: prepared by the authors from data provided by Wwoof Italy (2015)

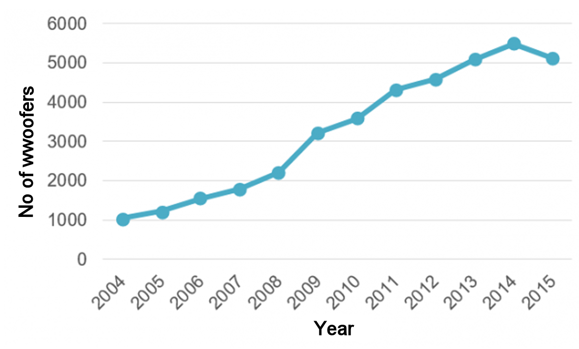

In the last 10 years there has been a significant rise in the number of national and international volunteers registered on the Italian website, from 1,000 in 2004 to over 5,000 since 2013 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Number of Wwoofers registered with WwoofItaly

Source: data provided by Wwoof Italy, 2015, and elaborated by the authors

The increase in the number of members and Wwoofers is mainly the result of word of mouth and only more recently due to the use of internet.

Structural and functional aspects of the network

Depending on the spatial proximity of the network nodes it may be possible to distinguish a primary horizontal network on the one hand characterized by direct and more frequent relationships, and a more extensive secondary network on the other, characterized by less frequent relationships, but connecting with the whole movement.

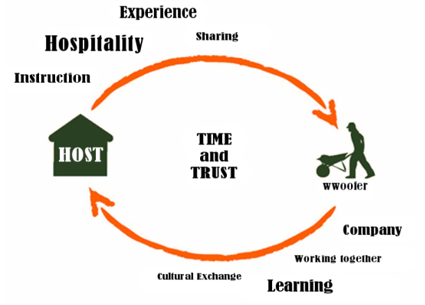

The primary network (Figure 3) created is that of close proximity and direct contact, which is established within the Learning Centre3 between the host and the Wwoofer(s) and consists of sharing everyday life, in which the volunteer participates in the life and work of the place, under the supervision and instruction of the host.

Figure 3 – The primary network relationships

Source: Prepared by the authors

The horizontality of the relationship is obvious from the Association's Internal Regulation: “Knowledge and experience will be exchanged taking into account the same life plan. This will take place without any form or subordination or remuneration and through a spirit of collaboration and conviviality in leisure and working time.” (Internal Regulation WI, article 5.1)

The value and the foundation of the relationship that is created by a Wwoofing experience can be defined, for all parties involved, by the term “free reciprocity” (Bruni, 2006) and may benefit both parties involved if specific actions find a purpose in virtuous deeds. To Wwoofers the experience offers the possibility to enter into a specific local rural business, the opportunity to learn about sustainable farming methods, to personally grow by working in the field and establish sincerity and trust in the relationship that is created with the host (McIntosh and Bonemann, 2006). To the host Wwoofing is a means to adapt his farm to change, maintaining its identity but changing its internal organization as needed for the management of Wwoofers, and offers the possibility to obtain a helping hand in pursuing his life project/work.

In some situations, in addition to this primary network, a network between farms develops as a result of the interaction and collaboration that take place between hosts in the same area.

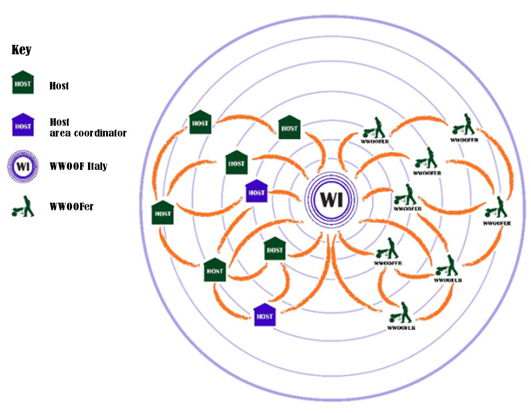

The primary network is then included in a larger network, of the informal secondary type, that involves and connects all farms participating in the Italian Wwoof movement and all volunteers registered with it. This is illustrated by figure 4, which shows, in a simplified way, the relationships within the informal secondary network.

Figure 4 – The informal secondary network

Source: Prepared by the authors

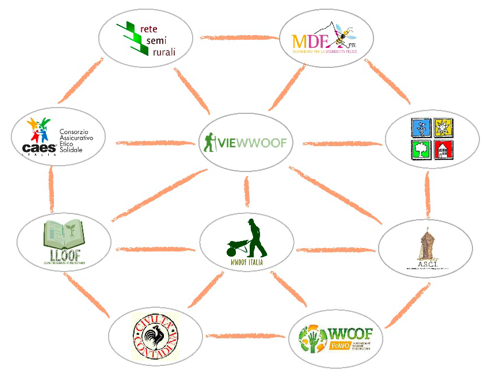

Over this network another, formal secondary network is placed, comprising the interlinking relationships that the WI Association maintains with civil society and other local and national associations (e.g. la Rete Semi Rurali, Banca Etica, il Movimento per la decrescita felice) to disseminate information, educate people and create awareness about sustainable and alternative agriculture. Figure 5 illustrates a possible representation of the relationships within the formal secondary network.

Figure 5 - The formal secondary network

Source: Prepared by the authors

An added value especially in contexts of rural "marginality"

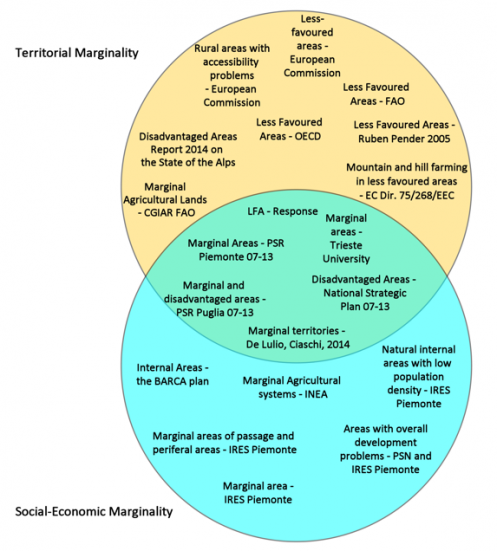

In a country like Italy, which is extremely diversified and predominantly mountainous or hilly, the protection and promotion of rural areas is crucial for their survival. These areas are often characterized by "marginality" or a complex set of disadvantages, due not only to unfavourable physical characteristics of the landscape, but today also to socio-economic and relational aspects, following the evolution over the past two decades of definitions provided by important organizations and institutions that deal with the issue at a national and international level (Figure 6).

The Wwoof movement, with Wwoofers searching for more awareness and alternative approaches regarding food, lifestyle and holiday-making, enables the sharing and promotion of resources that otherwise would not be mobilised because of demography, income, wealth and the distribution of services. In this sense, the movement is an exogenous incentive that offers an opportunity to break isolation and obtain internal as well as external benefits in the rural area in question.

Figure 6 - Classification of the “marginality” for the various institutions and research bodies

Source: Gasparetto, 2014

Final considerations

Being part of this network offers various opportunities, the most important of which are the spreading of knowledge in the form of information with educational value for the volunteers and the increase of the resilience and visibility of the farm for the hosts. The educational aspect of the experience is interesting because of the awareness for future choices made by consumers. In the daily activities the farmer gives the volunteer information, unreservedly offering the tools to transform theoretical knowledge into practical action; the volunteer applies what he has learned and contributes to the functioning of the farm, while acquiring knowledge he is unlikely to forget. You can therefore speak of citizen engagement to the extent that it is the active participation of citizens, that leads to producing their own food for a period of time and constituting a form of gaining new knowledge. Living in a place and being part of it through work and sharing, the volunteers acquire a different awareness of their actions, supporting the idea of DeLind (2002) for whom "it is in the inhabitation of a tangible and shared place, in the confluence of nature and culture, that environmental responsibility and sustainability take shape." In this sense, Wwoofing can be seen as a form of civic agriculture: practice and experience helps knowledge to take root and become part of consumer awareness, thus contributing to a rationality based on shared values (Di Iacovo et al., 2014).

Wwoofing offers businesses a possibility to maintain their resilience in their agro-ecosystem, adapting to change while keeping their essential functions. Wwoofing also offers an opportunity to increase a business’ visibility and expand the sales market to also include foreign countries, with a business card that in some ways may function as a certification4. In fact, citizens are offered a more direct knowledge of organic practices in various forms, providing the tools for a better understanding. Thus for example, the choice of organic products will not only be based on a brand and a certification, but can also be focussed on more informal and direct buying channels, where the consumer really has the confirmation that the food purchased was produced by sustainable methods. In this way the Wwoofing movement is an opportunity to maintain the viability of rural areas and open them up to the outside world, even more so for those in marginal conditions. In line with the emergence of new flows between the city and the countryside, it is becoming an example of how, through the creation of horizontal networks, the rural dimension can take shape (again but differently) thanks to forces from urban centres. An example that we believe merits further research.

Bibliographical references

-

Aguglia L. (2009), La filiera corta: una opportunità per agricoltori e consumatori, Agriregionieuropa 5(17)

-

Amin A. and Thrift N. (1995), Institutional issues for the European regions. Economy and society, n. 24, p. 121-143

-

Bourdieu P. (1980),Le capital social: note provisoires.. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n. 31, p. 2-3

-

Bruni L. (2006), Reciprocità. Dinamiche di cooperazione, economia e società civile. Bruno Mondadori

-

DeLind L.B. (2002), Place, work, and civic agriculture: Common fields for cultivation. Agriculture and Human Values, n. 19, p. 217-224

-

Di Iacovo F., Fonte M. e Galasso A. (2014), Agricoltura civica e filiera corta. Nuove pratiche, forme d’impresa e relazioni tra produttori e consumatori, Working paper 22, Gruppo 2013, [pdf]

-

Esparcia J. (2014), Innovation and networks in rural areas. An analysis from European innovative projects. Journal of Rural Studies, n. 34, p. 1–14

-

Gasparetto E . (2014), Aree agricole marginali: quali mezzi e tecnologie per le nuove forme di agricoltura su piccola scala? Tesi di laurea magistrale. Università degli Studi di Torino, p. 1-136

-

Latour B. (1986), “The powers of association”, in Law J. (eds.) Power, action, belief, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

-

Lowe P., Murdoch J., Ward N., (1995), “Networks in rural development: beyond endogenous and exogenous approaches”, in Van der Ploeg J.D., Van Dijk G. (eds.) Beyond modernisation: The Impact of Endogeneous Rural Development. Van Gorkum, Assen, The Netherlands

-

McIntosh A.J., Bonemann S. M. (2006), Willing Workers on Organic Farms (Wwoof): The alternative farm stay experience? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, n. 14(1), p. 82-99

-

Murdoch J. (2000), Networks - A new paradigm of rural development? Journal of Rural Studies, n. 16 (4), p. 407-419

-

Ravasi F. (2010), Wwoof (opportunità in “fattorie biologiche” nel mondo): Le potenzialità offerte da un’organizzazione che apre una finestra sul mondo agricolo attraverso uno scambio “umano”. Tesi di laurea triennale, Università di Pisa, pp. 1-108

-

Rossi A., Brunori G. (2011), Le pratiche di consumo alimentare come fattori di cambiamento. Il caso dei Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale. Agriregionieuropa 7(27), p.86

-

Sotte F. (2006), “Sviluppo rurale e implicazioni di politica settoriale e territoriale. Un approccio evoluzionistico”, in Cavazzani A. et al., (eds.), Politiche, governance e innovazione per le aree rurali, Inea, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, Napoli

Website references

-

Fowo: www.WWOOF.net/fowo/

-

Wwoof Italia: www.WWOOF.it

- 1. International Wwoof Association (IWA).

- 2. Data on Wwoof Italy were kindly provided by Claudio Pozzi, president of Wwoof Italy, in a telephone interview conducted in March 2016.

- 3. The place in which the exchange takes place as defined by the Internal Regulation.

- 4. According to data provided by Wwoof Italy only 10% of the participating farms has an organic certification, whereas over 80% claims to follow organic agricultural methods.